MOX Moves Secretly

DOE Dusts Democracy

By Bonnie Urfer

Environmentalists condemned it. Citizens and local governments won a

temporary federal restraining order against it. The Great Lakes Conference

of Mayors passed a resolution against the use of it. The International

Association of Fire Fighters didn't want to risk it. The city of Port Huron

passed a resolution against the transport, use or testing of it in the

Great Lakes Basin. The city of Nepean passed a resolution to prohibit the

transport, as did St. Clair County and the City of Buffalo. Michigan State

legislators Jud Gilbert and Lauren Hager, both Republican representatives,

introduced a resolution opposing it. New Democrat Party leaders Alexa McDonough

and Howard Hampton condemned the testing plans. State Rep. Andy Neumann

proposed a million-dollar fine for transporting the material across bridges

spanning Great Lakes water. The Department of Energy (DOE) was forced to

hold public hearings and scoping meetings, collect public comments and

face media scrutiny-all of which showed overwhelming opposition. What is

it?

It is "MOX" or mixed oxide fuel for nuclear power reactors, a mix of plutonium and uranium recovered from retired H-bombs. MOX is part of a first-time experiment called the Parallex Project in which the fuel rods - a blend of 97% uranium oxide and 3% plutonium-oxide - will be tested for two years in a Canadian Candu reactor. The DOE says the test is part of its so-called disarmament efforts with Russia. The U.S. is picking up the $20-million tab for the entire experiment.

First Nations across northeastern Ontario threatened to disrupt shipments of the plutonium, unless the federal government immediately consulted affected communities. "We haven't had an opportunity to have our concerns raised and addressed," said Earl Commanda, chief of the Serpent River First Nation. The North Shore Tribal Council and Mohawk elders condemned the proposed use of the Trans-Canada Highway, from Sault Ste. Marie to Chalk River, northwest of Ottawa, Ontario.

From the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, to Atomic Energy of Canada, Ltd.'s (AECL) laboratories at Chalk River, Ontario, citizens of Canada and the U.S. demanded warning that the plutonium was on the road. The DOE shipped it secretly.

Tracked by satellite, the unmarked tractor-trailer-carrying nine MOX fuel rods, including 4.2 ounces of weapons-grade plutonium-crossed the U.S. in January. The DOE sent armed guards with shoot-to-kill orders along with the shipment in what the DOE called "an enhanced security platform." The couriers, who normally transport atomic bombs and component parts, carry shotguns, assault rifles, pistols and night-vision goggles, etc.

Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility said, "It's a national disgrace that we are going into the 21st century with the same degree of secrecy and stupidity surrounding nuclear policy decisions, as we have experienced in the 20th century."

Two or three similar shipments of fuel are expected to arrive by ship

from Russia at the port of Cornwall on the St. Lawrence Seaway. The plutonium

is scheduled to be trucked from there to Chalk River. The Akwesasne Nation

vowed to use every means possible, even physical blockades, to prevent

Russian MOX from being shipped across its territory.

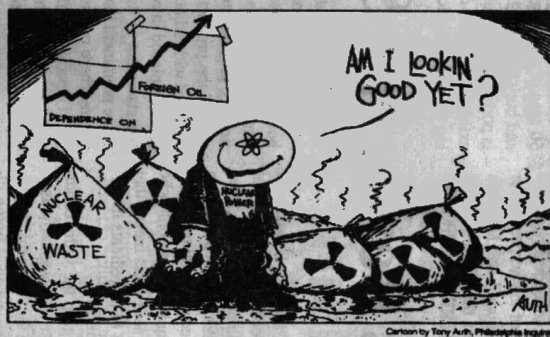

Both the U.S. and Canada claim that the MOX plan helps rid the world of weapons-grade plutonium. But the process in no way destroys plutonium, with its radioactive half-life of 24,000 years. Plutonium, used in fuel rods, creates a new stream of radioactive waste, making the long-term storage problem even more complex. Canadians have expressed concern about eventually becoming a dump.

Plutonium fuel rods may be used at Chalk River for 28 years provided testing is "successful."

***********

U.S. District Chief Judge Richard Enslen in Michigan issued a temporary restraining order Dec. 8 prohibiting the transport of MOX through the state. Opponents of the shipment moved for a preliminary injunction stopping all the shipments-U.S. or Russian-until a federal Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) could consider the consequences of a shipwreck, truck crash or fire. The order lasted just 10 days. DOE lawyers argued that delaying the shipment would "jeopardize nuclear disarmament treaties with Russia" and other countries.

This is a reference to the DOE's plan to process half of its 50 tons of plutonium waste into fuel (unusable for bombs), and bury the other half underground. The MOX fuel scheme is portrayed as disarmament when in fact it's intended to give extended life to the decrepit nuclear power industry by stretching the operating licenses of otherwise unlicensable reactors.

Judge Enslen's order considered: 1) whether the critics had a "strong" likelihood of preventing the DOE action because of the dangers involved; 2) whether the critics would suffer irreparable injury without an injunction; 3) whether issuance of a preliminary injunction would cause substantial harm to others; and 4) whether the public interest would be served by issuance of a preliminary injunction. The Judge answered no to all four questions.

Ironically, the court found that the National Environmental Policy Act was trumped by binding international deals?in this case the nuclear non-Proliferation Treaty. The court said that agreements made between Russia and the U.S. were an executive decision that should not be interfered with by the judicial branch. Attorneys Kary Love and Anabel Dwyer, nuclear weapons and international law experts who brought the suit, may have swallowed hard at that. Hearing a U.S. judge acknowledge the supremacy of international law is extremely rare in federal courts that, as a rule, pretend that international law is irrelevant.

For good measure, the judge dared to say that one MOX shipment did not pose a risk to citizens, as if his word sufficed as an environmental impact statement.

Enslen's 26-page ruling denied a preliminary injunction and vacated the temporary restraining order. Attorney's Dwyer and Love have asked for a formal reconsideration, and may appeal.

The DOE's load of MOX made it to the Canadian border Jan. 15. The mayor's office in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. called state activists to report that the shipment went across the International Bridge at 10 a.m. and then, amazingly, was flown by Canadian helicopter to Chalk River. While U.S. law forbids air transport of plutonium-over U.S. territory, the Ottawa government approved the switch from truck to helicopter

Risking a helicopter crash succeeded in evading public protests and an international confrontation on Native Nation lands, but flying may have been illegal in Canada too, according to critics including Tony Martin, New Democrat Party MPP from Sault Ste. Marie. Grounds for law suits are under investigation.

The Ontario Public Service Employees Union filed charges against the government under the Occupational Health and Safety Act for exposing workers. "The employees knew something was amiss only when they got to work and found the hangar swarming with 100 armed, sharp shooting police," said Robert DeMatteo, a union official.

The DOE then announced that it completed a "one-time shipment of a small quantity of mixed oxide nuclear fuel to Canada." Did the agency mean that future shipments would be large quantities? Hundreds of similar MOX transports are potentially heading for a site in South Carolina. The DOE's tactics this time indicate that the democratic process is threatened, not protected, by nuclear weapons.