Excerpted from A Pure, High Note of Anguish

The Los Angeles TimesSunday, September 23, 2001

by Barbara Kingsolver

I have some answers, but only to the questions nobody is asking right now but my 5-year old. Why did all those people die when they didn't do anything wrong? Will it happen to me? Is this the worst thing that's ever happened? Who were those children cheering that they showed for just a minute, and why were they glad? Please, will this ever, ever happen to me?

Yes, it's the worst thing that's happened, but only this week.

Two years ago, an earthquake in Turkey killed 17,000 people in a day, babies and mothers and businessmen, and not one of them did a thing to cause it. The November before that, a hurricane hit Honduras and Nicaragua and killed even more, buried whole villages and erased family lines and even now, people wake up there empty-handed.

Which end of the world shall we talk about? Sixty years ago, Japanese airplanes bombed Navy boys who were sleeping on ships in gentle Pacific waters. Three and a half years later, American planes bombed a plaza in Japan where men and women were going to work, where schoolchildren were playing, and more humans died at once than anyone thought possible. Seventy thousand in a minute. Imagine. Then twice that many more, slowly, from the inside.

There are no worst days, it seems. Ten years ago, early on a January morning, bombs rained down from the sky and caused great buildings in the city of Baghdad to fall down--hotels, hospitals, palaces, buildings with mothers and soldiers inside--and here in the place I want to love best, I had to watch people cheering about it.

There are no worst days, it seems. Ten years ago, early on a January morning, bombs rained down from the sky and caused great buildings in the city of Baghdad to fall down--hotels, hospitals, palaces, buildings with mothers and soldiers inside--and here in the place I want to love best, I had to watch people cheering about it.

In Baghdad, survivors shook their fists at the sky and said the word "evil." When many lives are lost all at once, people gather together and say words like "heinous" and "honor" and "revenge," presuming to make this awful moment stand apart somehow from the ways people die a little each day from sickness or hunger. They raise up their compatriots' lives to a sacred place--we do this, all of us who are human--thinking our own citizens to be more worthy of grief and less willingly risked than lives on other soil.

But broken hearts are not mended in this ceremony, because, really, every life that ends is utterly its own event-- and also in some way it's the same as all others, a light going out that ached to burn longer. Even if you never had the chance to love the light that's gone, you miss it. You should. You bear this world and everything that's wrong with it by holding life still precious, each time, and starting over.

And those children dancing in the street? That is the hardest question. There are a hundred ways to be a good citizen, and one of them is to look finally at the things we don't want to see. In a week of terrifying events, here is one awful, true thing that hasn't much been mentioned: Some people believe our country needed to learn how to hurt in this new way. We didn't really understand how it felt when citizens were buried alive in Turkey or Nicaragua or Hiroshima. Or that night in Baghdad.

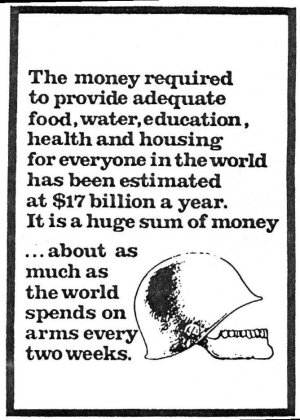

And we haven't cared enough for the particular brothers and mothers taken down a limb or a life at a time, for such a span of years that those little, briefly jubilant boys have grown up with twisted hearts. How could we keep raining down bombs and selling weapons, if we had?