His War for Peace

by Mike Kilen

Des Moines Register Staff Writer

September 19, 2002

The Rev. Frank Cordaro is out of jail and, for his flock, it's not a moment too soon.

With the U.S. on the brink of an expanded war, the Catholic priest and longtime anti-war protestor is in full throat, although he has promised the bishop to stay out of jail for a while.

"Oh God!" Cordaro says when he prays, his voice rising in an Italian inflection that is just this side of New York. "Help us in this crazy time to be lovers and not killers."

Fresh off his seventh prison stint for protesting weapons, war and the government that, he says, makes both, he has returned to the Catholic Worker House at 1310 Seventh St. to live in an upstairs room.

At a recent "welcome home" service and party, a rabble of poor neighborhood folks, church types from all parts of town, do-gooders and longtime anti-war protestors gathered in a large circle, glistening with sweat from the heat.

Cordaro was wearing not a clerical collar but a T-shirt. He sat next to Ed Fallon, the lanky liberal state legislator who squeezed out "When the Saints Go Marching In" on his accordion to the following edited verse:

"When Father Frank . . . comes home at last.

"His stand for peace we'll cell-e-brate

"And we'll prayyyy that war will be endedddd

"When Father Frank comes home at last.''

Father Frank, as he is often called, is known across Iowa for his 25 years of protests. A recent book on priests as war protesters ranks him among the most significant handful in the country.

Cordaro is habitually in trouble with the church. He promised Bishop Joseph Charron he would stay out of jail for two years and tend to pastoral care.

Stay clean for two years, Charron told him. No more jail time after this - and keep your trap shut when you disagree with church teachings.

Some Iowa Catholic priests wonder just what Cordaro accomplishes behind bars, especially with a priest shortage.

As is his custom, Cordaro, 51, will tell you with conviction and plain street language. No one, he tells the group, wants to be cowardly in the face of injustice.

Time and again, he steps across the white line at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha, knowing that he will be arrested, knowing that months of strip searches, bland food and tension-filled prison life will follow. He has spent nearly four of the last 25 years in prison for his protests.

After crossing the line at Offutt last August, he suffered a heart attack. When he recovered, he was sentenced in March to six months for entering military property.

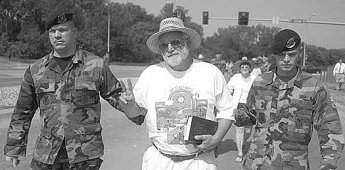

His fellow protesters at the Catholic Worker House called out their blessings as he was led away.

Cordaro helped start the Catholic Worker community in 1976 after he dropped out of seminary because he was romantically involved with a woman.

Des Moines was in his blood. He grew up here, the patriotic and athletic Catholic boy of Italian-American parents. His father served in World War II and received a Purple Heart, and was a coach and athletic director at Dowling High School.

On the day of Frank Cordaro's first Holy Communion, a special time for Catholic children, his father had a heart attack. He survived to remind his children of the bad in war and teach them to live each day to the fullest.

He died at age 47 on Easter Sunday morning, 1969.

"Don't worry, Dad," young Frank whispered in his ear before he died, "God will take care of everything.''

The politically charged days in college during the early 1970s didn't lead him away from the philosophy he shared with his father but toward a more active practice of his faith.

He wanted to follow in the footsteps of Jesus.

"Jesus was an act-up guy,'' Cordaro says. "He ran a political street demonstration in Jerusalem.''

With his customary down-to-earth spiritual wit, he sent his reflections from the federal prison in Duluth, Minn., to some 500 people on an e-mail list: "Most folks attending Easter services are not aware that the very act of the Resurrection was an act of civil disobedience. When the state orders a person executed, they are supposed to stay dead.''

Jesus surrounded himself with the poor, so helping start the Catholic Worker House was a logical move for Cordaro. The house is open for folks to gather and eat free meals in the poor north Des Moines neighborhood. It also was the beginning of challenging church rules.

He has said over the years that the church should not only take stronger positions against war but allow women to be priests and rethink its stands on birth control and homosexuality.

He thought his girlfriend would have made a fine priest. After the relationship with her ended, he became an ordained priest in 1985.

He has since been silenced on his open criticism of the church.

Bishop Charron of the Des Moines Diocese said Cordaro "made a promise when ordained to publicly uphold the teachings of the Catholic Church.''

One thing he refuses to quiet is his protest against violence. He'll even break the law to do it.

It started in 1978 at age 27. Cordaro and 27 others lay on the railroad tracks at the Rocky Flats plant in Golden, Colo., to protest the manufacture of nuclear weapons.

Since then, Cordaro has become a headline-grabbing force. In 1979, he stood 10 feet in front of President Jimmy Carter, who was addressing a group on the arms treaty, raised his arms and yelled protest to him in a loud voice while dropping ashes to symbolize what nuclear weapons will do to people.

He has bashed B-52 bombers with hammers and spilled blood on the Pentagon. He has become an Iowa celebrity of sorts with such actions and admits that "being meek and humble does not come easy for me.''

Some bristle at being called his "followers.''

"I want to make this clear,'' said longtime protestor Brian Terrell of Maloy, who met Cordaro at Rocky Flats and was at Cordaro's welcome home celebration.

"Frank is a friend, he is not a boss. We all make individual decisions based on our life situations.''

His often obsessive personality can challenge those he works with at Catholic Worker House. Once, the staff had to remind him that their role was to feed the poor after he turned away two hungry men at closing time because he was intent on preparing for a service.

Cordaro apologized. He says life at the Catholic Worker House keeps him humble while he tries to address the world's big issues.

"He tells us the basics we don't get in church, like thou shall not kill,'' says Mike Palecek of Sheldon, co-author of a new book on the lives of anti-war priests, "Prophets Without Honor.''

"You can go to church all year long and not hear that.''

Cordaro says the Catholic Church "doesn't know how to be a church of peace; we've been a church of war for so long.''

He challenges its doctrine of support for a "just war,'' which says war could be justified in the church's eyes if it preserves peace and protects human dignity.

Cordaro says that to follow Jesus, the church should forward an unwavering strict stance of nonviolence.

But what of the wars against an evil like Hitler?

He says leaders have used World War II to justify violence against nations. That war was caused by World War I, he says, and all military action since then has been "empire building.''

"If someone looks to get an equal share, we kill them,'' Cordaro says.

So he continues to cross the line, year after year. Even after a heart attack. Even, at times, when church leaders have threatened excommunication.

"It's an act of conviction,'' he says. "Every time a judge tosses us in jail, it helps us make our point.''

It also costs society an average of more than $60 a day to house an inmate in a federal prison. Cordaro says war-making weapons, in contrast, run in the billions.

Some priests say he has gone too far.

"You can be a total pacifist and let them kill us. Or you can fight them; it is not un-Christian. There are just wars,'' says Father John Harmon of St. Ann's Catholic Church in Logan, Ia.

"I don't see what going to jail accomplishes,'' he continued. "We have this shortage of priests and people need to be ministered to.''

Cordaro says he does some of his most meaningful work with inmates in prison. Mothers of cellmates cry with joy when they find out he is a priest. Hardened criminals have poured out their stories to him.

People love to hear him preach and embrace his tough talk.

"Even though I'm a lawmaker, I'm in total agreement with this lawbreaker," says Fallon at the "welcome home" service and party.

While Cordaro awaits assignment to a parish, war looms and his promise of silence appears tenuous. He considers himself a prophet in the tradition of Jeremiah, whose heart burned in the face of injustice: "I grow weary of holding it in. I cannot endure it.''